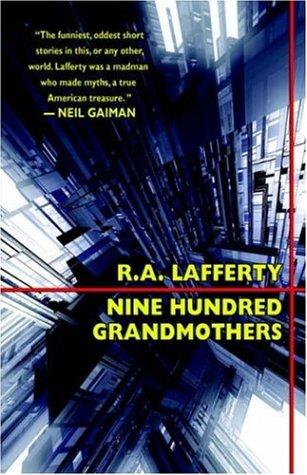

“Nine Hundred Grandmothers” is a tale about origins, about How It All Began, and as such serves well both as introduction to the anthology of the same name, and to our investigation of Lafferty’s short fiction.

The story is about as straightforwardly science fiction as Ray ever gets. It doesn’t blur genre boundaries. It makes no formal innovations. It doesn’t even have an apocalypse, rather something more like an epiphany in one of Joyce’s Dubliners tales.

And yet it was one of his more daring stories. In “Nine Hundred Grandmothers” Lafferty takes on the colonial SF tale, a subgenre wildly popular in the previous generation, and still with advocates among the editors of the early ’60s. This type of story, the descendant of Victorian adventure fiction, usually takes place on a commercially promising territory; here, Proavitus is “a sphere tinkling with the profit that could be shaken from it.”

So a hypermasculine expeditionary force, the pride of vintage sf, is sent to shake it. Led by Manbreaker Crag, and with a cast including Heave Huckle, Blast Berg, and George Blood among others, it is a group that is “supposed to be tough, [so] they had taken tough names at the naming”—all except their cultural officer, Ceran Swicegood, who keeps his original name. This disgusts Manbreaker: “Nobody can be a hero with a name like Ceran Swicegood! Why don’t you take Storm Shannon? That’s good. Or Gutboy Barrelhouse or Slash Slagle or Nevel Knife? You barely glanced at the suggested list.”

Lafferty here suggests the sort of list a novice writer might consult when trying to prove that his characters are tough enough for the genre—or even when trying to find something for himself that will look good on a magazine cover. Ceran, however, resists this renaming, and is as yet an imperfect fit for the colonial sf story: the narrator notes that, “Had [he] assumed the heroic name of Gutboy Barrelhouse he might have been capable of rousing endeavors and man-sized angers rather than his tittering indecisions and flouncy furies.” This imperfect masculinity resigns him to the role of cultural officer, leaving him to consult with the natives; his counterpart among the Proavitoi is “likely feminine”—there is a “certain softness about both the sexes” there that bodes ill for an expedition member who has not firmly established his manhood before touching down.

Ceran Swicegood’s primary failing is his concern with time. Stories about aliens and astronauts rarely bother much with time: they take place in the future, and their heroes act in the present. But Ceran, with his “irritating habit [of] forever asking the question: How Did It All Begin?”, is inexplicably concerned with the past, to the point of even refusing to give up his own in the naming. So when he is put on the tip that the Proavitoi do not die, and moreover that they have a Ritual that passes along from the very oldest the origin story of the universe, he believes he is finally near to answering his burning question. But this viewpoint is unsuited for an expedition man, who should already have had his orientation toward time fixed in the Ritual of the naming. As Manbreaker Crag tells him, “It don’t make a damn how it began. What is important is that it may not have to end.” For Crag, this is a Fountain of Youth story, a chance to gain an immortality that will allow for neverending conquest and plunder, delivered in regular monthly installments.

But Ceran, perversely, seeks to get beneath the surface of this pulp standard fare, and he ventures into the caverns underneath Proavitoi in search of the eldest of them all. The title “Nine Hundred Grandmothers” refers to the regression of ancestors, as Ceran goes ever deeper into their memory of the past. When he reaches bottom, he is confronted with the one thing the hypermasculinized sf narrative cannot abide: laughter. “Oh, it was so funny a joke the way things began that you would not believe it,” says the ultimate grandmother, and Ceran’s exasperation grows as they all seem too caught up in laughter to actually answer him.

But the laughter is their answer: as Mikhael Bakhtin notes in his study Rabelais and His World, “the characteristic trait of laughter was precisely the recognition of its positive, regenerating, creative meaning … in an Egyptian alchemist’s papyrus … the creation of the world is attributed to divine laughter.” During the time of Ritual, that primal laughter still echoes in the caverns. “How good to wake up and laugh and go to sleep again,” the grandmother says; for her, and for all Proavitoi, laughter is both carnival and “the expression of [their] historical consciousness.” It is a consciousness alien to the astronaut: Ceran flees, “we[eping] and laugh[ing] together.” Having failed at Ritual, unable to discern the answer to his question even as it rang out all around him, he undertakes instead the ritual of the naming, adapting himself to a serialized, dehistoricized existence: “On his next voyage he changed his name to Blaze Bolt and ruled for ninety-seven days as king of a sweet sea island in M-81, but that is another and much more unpleasant story.”

Ceran Swicegood/Blaze Bolt is in some ways, then, like those ’60s pulp-SF writers or editors, seeing the changes at work in the field, but ultimately refusing to take part, fleeing into the thrilling, threadbare comforts of pulp SF convention. When he goes, we do too: the asteroid Proavitus (Latin for ancestral) is closed off to us forever, with Lafferty never returning to it again.

In this there is, possibly, a rebuke for the newer generation of science fiction just then emerging. Only four years before “Nine Hundred Grandmothers” was published—two years before Lafferty typed the manuscript—J.G. Ballard was issuing his famous call for the exploration of “inner space.” That is exactly what Lafferty provides here: an early example of his obsessions with two- and three-dimensional spaces. The Manbreaker Crags live for the surface alone, for what can be shaken out of a place; the Ceran Swicegoods, though, are Ballard’s explorers, delving into the depths in search of their own beginnings. And in many of Ballard’s stories, these explorers come to the very same end: after some sort of epiphany, they suicide, or are changed beyond even the persistence of a name.

Lafferty supports this venture into ourselves, into our own stories, but differs in his insistence that we then bring back some of that cosmic laughter to carry out with us into the stars. Otherwise when we flip the page, we will become all so many Blaze Bolts, filling more pages, shaking more worlds, heroes of a much more unpleasant story.

[Andrew Ferguson has written the first academic paper on R. A. Lafferty: ‘Lafferty and His World’. It is a lengthy, learned, and thoroughly thrilling read. (If you find some of the technical, academic language too much to swallow initially, I personally would recommend skimming through to the next mention of a story or novel. There are as many accessible insightful moments in the paper as there are more difficult passages. It’s full of gold.) Andrew also manages the Lafferty wikidot page: The Institute of Impure Science, Online. This is a work-in-progress that is attempting to state the summary, setting, and characters of every single one of Lafferty’s short stories, thus demonstrating the overlapping, ‘hypertext’ quality of the worlds Lafferty created.]

17 comments:

I had never consciously thought before about the metaphor linking Ceran wandering back into the caves under the Proavitoi house and delving deeper into the psyche. Not because it wasn't obvious--it is. It just fits so well that I never thought to examine it.

I think you are exactly right to show this story as a transition between pulp SF and the beginnings of the New Wave SF. It shows a rejection of the tropes of the "Golden Age" and an attempt to focus on the mysteries of the psyche. But which one is it mocking?

I would echo Kevin’s comments as well as his question concerning the target of Lafferty’s humor. Certainly, “Nine Hundred Grandmother’s” is one of the most hilarious responses to militaristic pulp SF ever penned. In his excellent analysis Andrew rightly emphasizes the “positive, regenerating, creative meaning” inherent in laughter, as Bakhtin eloquently explains in his chapter on Rabelais in the history of laughter; but I would also want to emphasize the subversive power and function of humor, particularly the grotesque variety practiced so well by Lafferty, to critique social structures and received ideologies. I would argue that as the 60s progressed into the 70s and 80s, much of Lafferty’s attention turned towards those very social changes that allowed the New Wave and other literary and artistic experiments to flourish (not only within the narrow confines of SF, but in the wider fields of the arts, and indeed in society as a whole), and increasingly made these newly emerging social structures the target of his biting satire. Perhaps this goes some ways to explaining Lafferty’s uniqueness within the genre, as well as his ongoing relative obscurity: while Lafferty is one of the supreme exemplars of the New Wave, he is also one of the most trenchant critics of the social mores and ideological tenets to be found in many of the New Wave’s other practitioners. This is the Lafferty paradox (or at least a significant aspect of it)—the fact that Lafferty is often most at odds with his most ardent admirers and defenders and their entire worldview. This state of affairs is perfectly captured in a quote from Harlan Ellison, who wrote quite tellingly in a tribute essay “Ray Lafferty contends I’m in the paid employ of the Antichrist. Nothing I can say will convince him otherwise. I’m resigned….Nevertheless, I wildly admire Lafferty’s work.” As Lafferty aged, he grew increasingly alienated from the world he saw emerging around him. And not just the world of Science Fiction. This alienation is especially evident in the case of the various theological changes he saw taking place within his beloved Catholic church. In fact, some of his blackest humor and most biting satire are employed in mocking post-Vatican II Catholicism, particularly in later works such as More Than Melchisedech and “How Many Miles to Babylon.”

Great analysis, Andrew. It's great to see some points from your long and professional dissertation being distilled more popularly. I especially love how you relate this story to standard pulp s.f. (as you do even more in the dissertation). And your comments about (the aptly phrased) 'cosmic laughter' were a real light turning on for me when I first read this in the dissertation, how the answer was ringing out all round Ceran but he wasn't prepared to perceive that.

I don't think there's anything I'd disagree with in Andrew's commentary, but there are qualifications and clarifications I'd want to make. In addition to Gregorio's helpfully balancing observations, I want to say also that, yes, it is increasingly clear to me how much Lafferty was exploring the human psyche, yet I think he's doing far more than this.

First of all, in addition to psychology he's also hugely exploring *philosophy* - philosophy of history, ethics, epistemology, philosophy of mind, metaphysics, political philosophy, aesthetics, poetics, and so on. And I do mean he's really exploring these things in some depth, repeatedly.

Also, there's not a little *theology*. The point being that Lafferty is exploring *outward* as much as *inward* and we can be in danger of misrepresenting him as slightly subjectivist or even solipsistic or narcissistic if we over-focus on his psyche-diving. Indeed, sometimes, more than 'exploring' inner space, I almost feel he's just heaping up huge handfuls of it and throwing it out on the world in carnival fun. An inward motion for the sake of going outward.

The words 'reality' and 'transcendence' come up again and again in Lafferty's fiction as things to be pursued above all else. 'How It All Began' is a real question for Lafferty that he wants us all to ask with metaphysical realism, not just personal narrative self-analysis. The 'cosmic laughter' is indeed *cosmic* - that is, universal, a thing 'out there', not just 'in here'. And to say so is a HUGE and radical worldview claim that I'm not sure any of the New Wavers could embrace (I recall Brian Aldiss in particular engaging Lewis's cosmic glory sort of view in his s.f. trilogy and respectfully declining, saying of the universe, 'I think it's cold out there' and ‘we’re alone’).

And ‘Ritual’ in this story also points to that outward, revelatory, historical element that is required (according to Lafferty) to hear the truth of the cosmos, to be in on the ‘joke’ and laugh along. (As Andrew points out when he notes that Ceran becomes dehistoricized in the end.)

So yes, as Gregorio pointed out, there is both resonance as well as tension between Lafferty and the New Wave that fostered his emergence.

See Andrew's paper, p. 37, where he follows his discussion of 'Nine Hundred Grandmothers' with an excellent discussion of Lafferty’s short story 'Flaming Ducks and Giant Bread', which in its turn critiques at least the hippie-ish 'Summer of Love' elements of New Wave s.f. Andrew notes that Lafferty is saying: 'freed from the endless repetitions that characterize the Blaze Bolt style of science fiction, the citizens of Love are yet content to remain on the surface'.

http://virginia.academia.edu/AndrewFerguson/Papers/288013/Lafferty_and_His_World

Daniel, I couldn’t agree more with your point about Lafferty not being a subjectivist. As you say, if he explores inner reality it is only because it reveals something profound about the order of existence itself. This is closely allied to my comments on the function of laughter in Lafferty: while there is a mocking or satirical dimension to Lafferty’s humor that should not be overlooked; the more important elements is that creative laughter that Andrew focuses on in his analysis of “Nine Hundred Grandmothers.” Humor is used, then, not merely to laugh at human folly, but also creatively point towards the joy to be found in ordered existence (Lafferty almost invariably depicts the opposite of true laughter and happiness as being uncreative disorder or humorless chaos, for example in “Ishmael into the Barrens”).

These points are I think particularly evident in the novel Aurelia. Here I think it is easier to see than in some of other writings that Lafferty is not merely decrying the excesses of 60s culture, or pointing out certain negative trends in modern society, but also attempting to articulate a fully worked out alternative vision of society in a series of sermons delivered by the title character, a social vision that Lafferty draws quite explicitly from his close reading of Thomas Aquinas. Needless to say, the book is also full of Lafferty’s quirky humor.

I won't add anything to your first paragraph. Agreed.

AURELIA! Just finished it the other day and was so taken by surprise with the sermons on Thomistic Virtue Ethics and the rather sad poignancy of the book. Whereas so many other of his novels are an Apocalypse, this one felt more like an Advent. It also has maybe the very best and most biting of his socio-political satire I've seen, but with loads of grace and compassion. It's also very weird, at times grotesque and at times full of wonder and humour. I felt it made explicit Lafferty's real love for his world, no matter how angry he was with it at times. Something I've always known implicitly from his fiction, but this really brought it out for me. Aurelia really deserves to be far better known.

I only read Aurelia a few months ago after Andrew Ferguson suggested that, with my background in Thomism and interest in Lafferty’s theological vision, I should take a look at this neglected work. I have to admit I was completely floored by it!

I also got the feeling that rather than falling in the Apocalyptic genre, there is a strong element of Advent –as you describe it – present in the book. But I would carry that analogy further, and propose that with its extended sermon on the mount/plain – culminating in the sacrificial death of its innocent almost Messianic protagonist – that the novel is actually Lafferty’s attempt at another biblical genre, that of a Gospel. At the very least, the story reminds quite strongly of early apostolic martyrdom accounts, where the martyr’s life and death are closely modeled on that of Jesus.

Oh man, Gregorio, a *Gospel*! You just blew my mind.

What I love about it too is that I think it's one of his better written books - I don't see how any Lafferty fan, of whatever philosophical/theological persuasion, wouldn't enjoy the story and pathos and Laffertian quirkiness.

To me it feels narratively somewhere between the likes of Space Chantey and Reefs of Earth, which are novels that I think clip along fairly well.

So that it's potentially a sort of Gospel-genre book too, just closes the deal for me. And it shouldn't be surprising that a compelling read goes together with Gospel matter as the Four Evangelists are hugely compelling reading in any light.

Listen, you've just gotta give us a wee review sometime of Aurelia as a guest blog post. You're the man for the job. Even if it doesn't happen for a LONG time. (And do tell me more about your background in Thomism sometime!)

I’ve been lucky enough to have the opportunity to earn a B.A. in philosophy in a program that was designed in a traditional Aristotelian-Thomistic point of view (i.e. a strong emphasis on metaphysical realism, the correspondence theory of truth, virtue ethics, the analogy of being, etc.), then an M.A. in historical theology focusing on Patristic and Medieval theology (my master’s thesis was on the concept of transcendental multitude in Aquinas’ Trinitarian theology). I’m currently a doctoral candidate at Marquette and in the beginning stages of writing my thesis, an analysis of Thomas’ Christology; I’m also an adjunct professor teaching undergrad theology courses.

I started reading Lafferty long before I went to grad school, but I would have to say that my training in philosophy and theology has completely transformed my appreciation of Lafferty’s work. For one thing, even though Lafferty never went to college, he had a very thorough religious education at the primaryand high school level(a state of affairs more common in pre-Vatican II Catholic schools than it is now), supplemented by his astonishing personal reading program. Lafferty was a life-long autodidact, and it has taken my pursuit of a Ph.D. to even begin to understand some of what Lafferty was doing in his works at the philosophical and theological level.

For some time (in between school work and other responsibilities) I’ve been doing extensive research for a comprehensive analysis of Fourth Mansions, a novel which contains some of Lafferty’s most extensive engagement with the history of Catholic theological thought, a topic which I think is insufficiently appreciated even by many of Lafferty’s most devoted readers. My hope is to produce a study that will at least begin to explicate this long-neglected dimension of his thought. As you well know, Andrew has conceived the absolutely wonderful idea of putting together a book of Lafferty criticism, and I would love to see this study of Fourth Mansions published there.

As for your very generous invitation to do a guest blog review of Aurelia, the temptation is too strong for me to refuse. Although I could not actually start work on it until I make good on a number of other writing assignments which I have already committed to --- but I think you already understand that. I can foresee that a good portion of the review would deal with the profound ethical and social concepts (and their basis in Thomas)enunciated in Aurelia’s sermonizing. I would also have to expand upon my comments on the novel Aurelia as an example of the Gospel genre. But I think you could probably do an excellent job on that theme as well.

Gregorio (and Daniel and Andrew and Jay), I feel humbled in your presence. I am a technical writer and a dad and a joyful reader of New Wave SF and Lafferty. I love dabbling in literary analysis, but I can not pretend to being more than a dabbler. That being said, I'm too fond of talking about Lafferty to keep quiet.

In response to your description of Lafferty as an autodidact. I remember reading in an obituary how Lafferty's priest had the utmost respect or perhaps awe for the man's knowledge of theological works. The priest would work very hard on his sermons, and then deliver them only to see Lafferty sitting in the back of the church slowly shaking his head.

Kevin, I actually feel the same in the presence of all these MAs on their way to PhDs! I feel like a bit of a fraud, ha! But I'm so glad we have both types commenting on this blog right now. Laff's readership clearly spans that spectrum and the discussion is utterly enriched by ALL who come at it with the least hint of coherent thought and grammar!

I myself am a 'mature student' at university (a 37-year-old second-year undergrad in Eng Lit and Philosophy). I'm something of an autodidact myself (not remotely in the league of Lafferty), but my self-education is hugely scattered and unconnected, full of holes. So I'm finally trying to correct that by going through the recognised institutions (glad I've waited this long in some ways, though - helps to have some life experience and be able to think outside-the-institution a bit).

I'm really first and foremost a writer of verbose song lyrics for many years in punk rock bands (4 albums worth out there), subsequently slowly transitioning into fiction-writing. But as anyone can see from this (and my many other) blogs, I'm a BIG MOUTH, full of opinions that won't hold back. (And I really do find literary analysis one of life's more exquisite pleasures.)

Oh, and to complete the picture I should probably mention that I'm an 'ordained' low-church evangelical-charismatic 'pastor' of a small 'church plant' that meets in our home - with no formal theological training!

I enjoy reading your posts as well as the comments from Kevin, Jay and the other visitors to the site. I usually learn something new about Lafferty, or gain a fresh insight, or new way of looking at some aspect of his work that I was already familiar with. When I first started researching Lafferty (before that I was just a simple awestruck fan) I think I was looking for some sort of unitary understanding of Lafferty. In other words, one conceptual scheme or grand unified theory that would fully explicate all the things that intrigued and puzzled me about him. But it didn't take me long to come to the conclusion that Lafferty is too vast to be completely explained by any one such theory. So now I appreciate the fact that Lafferty Studies (Lafferty’s accomplishment seems to be broad and deep enough that he merits his own distinctive field of study) must be a multidisciplinary and collaborative undertaking. I’m pretty sure this is also Andrew’s point of view; otherwise I don’t think he would be working in putting together a collection of essays on Lafferty. And I see this blog as a nascent incarnation of the department of Lafferty Studies, a potentially much wider project benefitting from all the different points of view that the various contributors bring to the forum.

@Gregorio: 'a multidisciplinary and collaborative undertaking' - definitely! Thanks for your encouraging words. I would do this blog no matter what but it's been a huge pleasure and privilege to experience a wee community of Lafferty discussion. I do so hope we can all meet up in a few years or so at the first Lafferty convention or some such thing!

Your brief description of the Thomistic perspective sounds friendly to a lot of where I'm at. I so look forward to reading your Fourth Mansions essay someday. Delighted you'll do the Aurelia review sometime (no problem at all on timing - whenever it happens it happens).

@ Kevin: great anecdote on Laff and his priest. Source please?

@ everyone: I should maybe note here that not every review/meditation/intro on a short story as a guest blog post needs to be as academically sophisticated, nor even as lengthy, as Andrew's excellent first contribution. Our backgrounds and interests and level of skill and ability should definitely be reflected in our distinct voices. These aren't going to be the definitive essays on these stories - as I'm sure we all know! Just starting points for discussion. I seriously thoroughly enjoy and benefit from the comments of each one of you on these threads, so I have total confidence that your given short story meditations will be perfectly interesting and satisfactory.

All-- very interested in the discussion thus far and very much looking forward to your own intro posts.

Glad to see the return, here and in East of Laughter and elsewhere, to the laughter that pervades Lafferty's work. SF has a reputation as the most humorless of genres, in part because it is often the least human(e) as well. And of the SF writers who make me laugh, Lafferty is the only one to do so in this affirmational, cosmic way—Sheckley is cut with so much bitterness, Ballard with bleakness, Russ with great sociopolitical concerns, Douglas Adams with a sort of resignation.

Rabelais is the great master of this mode, sadly lacking not just in SF but in contemporary English letters generally (Sterne might be the greatest Anglophone example). Salman Rushdie manages it often enough, and Pynchon gets there sometimes, but I'm not sure who else among the living I could point to.

Chesterton makes me laugh in a world-affirming way. But I guess he's from an earlier era than what you're thinking of. (Also, Flannery O'Connor's dark 'Southern Gothic' tales are really carnival comedies of grace and redemption.) I think Neil Gaiman *tries* to take up this mantle from Lafferty to some degree - with what degree of success I'm not sure. (He's certainly not of the literary caliber of Lafferty and I think he readily acknowledges that - though he is good and enjoyable to read.)

But Chesterton is the only other writer that comes to mind who has the refulgent *joy* undergirding his writing that Lafferty has.

The connection made here between laughter and creation reminds me of similar points made by Tony Esolen in his book "The Ironies of Faith: The Laughter at the Heart of Christian Literature." Have you read that work--I highly recommend it if you have not read it. Esolen never cites Lafferty (he may not even be familiar with him), but many of his comments could easily apply to Lafferty's created worlds and theological understandings.

cheers,

Craig

Thanks, Craig! I just added it to my amazon list.

Post a Comment