The only exceptions I can think of are the utterly absurd and freakish Solomon Izzersted (a baseball-sized talking growth on the belly of another character) and the comically creepy human-faced bats, the Sussex Wraiths. But these two anomalies are seen, significantly, to be grotesquely self-important interlopers who have to be taken down a notch.

Lafferty assembles these beings out of fairy tale and juxtaposes them with certain modern entities and amenities: scientists of various sorts (biologists, nuclear physicists, and so on), intelligent personal computers, newspapers, and ‘modern world transport’ devices (instantaneous teleportation units in wealthy homes). This is the scenario Lafferty has created and he sticks to it. And whereas the world of any given story or novel by Lafferty is very often open to the presence of at least one alien entity (if not outright taking place in the deeps of space or on another planet), here no such characters or elements are allowed to intrude. Indeed, the interloping ‘neo-scribbling giants’, the Sussex Wraiths, suggest at one point that they thought the ‘writing of the world’, which is the philosophical subject of the novel, should include a scenario of extraterrestrials controlling the earth—and this is rejected out of hand. Lafferty has dealt with aliens, alien worlds, space travel and so on in many other novels and stories. This one sticks strictly to a closed-system earth that needs to clean up its own self-contained trouble (‘closed’ only in the interplanetary or intergalactic sense, obviously—not in terms of the supernatural or paranormal).

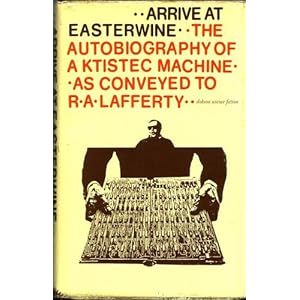

Indeed, East of Laughter may be Lafferty’s one Fairy Tale or High Fantasy novel (albeit in a modern setting – I’ve heard this called ‘mythpunk’). The rest of his novels seem to be science fiction of one sort or another (e.g. Past Master, Reefs of Earth, Space Chantey, Arrive At Easterwine, Aurelia, Annals of Klepsis) or historical fiction/fantasy (e.g. Fall of Rome, Okla Hannali, The Flame Is Green) or contemporary ‘urban fantasy’/‘magic realism’ (e.g. Fourth Mansions, Apocalypses, The Devil Is Dead). In terms of science fiction, it’s interesting that East of Laughter is about the ‘writing of the future’ and whether there will be a real future, but it finds the key to ‘futurology’ in a correct understanding of and continuity with history and fable.

Of course, Lafferty here is really just bringing to the fore the fairy tale aspects that were latent in much of his fiction all along. Think of how many stories and novels have a human character who is described as a goblin, giant, or witch, for example (Past Master, Arrive at Easterwine, The Reefs of Earth, Fourth Mansions, and The Fall of Rome all spring immediately to mind).

To some degree I think in East of Laughter Lafferty was going back and more explicitly reiterating: by the way, before we get to spaceships and aliens, we need to be sure we don’t leave behind all the wonderful and woolly myths that got us there. Indeed, in the midst of our Brave New Worlds of Artificial Intelligences and so forth, let’s keep it peopled with the whole crew we’ve had from ancient times and infused with aspects of the worldview(s) they represent. Otherwise we’ll find the whole show pretty empty, from the sketchy nations and landscapes right down to the emaciated and insipid atoms and musical notes. As Bertigrew Bagley, the Patrick of Tulsa, says in Lafferty’s novel Fourth Mansions:

‘Somehow there is the belief that people in the Dark Ages believed that the world was flat. They didn't. But it is the contemptuous ones of today who have made a really flat world that is the sad answer to everything. What is wrong with the world and why is it not worth living in? It's flat, that's what.’ (p. 59)

Don't you DARE judge this book by its cover!

The Laughing Christ Will Renew the World (Mythological Beings Included)

In connection with the Fairy Tale theme of East of Laughter it is interesting to note the Sylvan Spirit, one of the last living Fauns, who steps out of the Laughing Christ icon. This scene seems to resonate with a similar notion to what C. S. Lewis held: that the best of paganism is ‘hid in Christ’ and finds its true meaning and flourishing in him, especially at the renewal of the world.

Compare the scene in Prince Caspian where the children remark that they’d be afraid to be around Bacchus if it weren’t for the presence of Aslan—under whose rightful kingship the pagan god and his elfish crew flourish and rollick as part of Aslan’s renewal of Narnia back out from under the materialistic reign of terror it has endured. (These are themes to be found in Tolkien and Gene Wolfe as well.)

This viewpoint answers well to Lord Dunsany’s poignantly satirical tale, ‘The Development of the Rillswood Estate’, about the ignominious treatment of a satyr in the modern world, who can only survive and ‘get ahead’ if he modernises—in this case by marrying well and becoming a successful and rather fancy financier. Where the wonderful fantasist Dunsany seems to consistently find modernism repellent to his beloved paganism, Lewis, Tolkien, Lafferty, and Wolfe are in agreement. But they are not stuck with lament and lampoon and lambaste only. Lafferty and the others find (perhaps in what would be the most unexpected place to some) a certain sort of redemptive, sanctifying safe-house for mythical beings of paganism in the midst of the paltry modern world: the Church and her Lord. (See Lewis’s essay ‘Myth Become Fact’ and the Epilogue of Tolkien’s ‘On Fairy Stories’.)

Interestingly, I found this constantly recurring person-statue a rather side-note and comic figure on first reading East of Laughter. Later, I found him still creeping up on me, in a way that faintly and strangely resonated with Flannery O’Connor’s character in her novel Wise Blood who is haunted by Christ as ‘the ragged figure who moves from tree to tree in the back of his mind’. Sure enough, when I went back and re-read the Laughing Christ passages, I realised how subtly central he was.

The marble statue was ‘the greatest of Denis Lollardy’s forgeries’ (it remains a mystery whether or not there was a 5th century original). Early on we are told that it ‘cured the melancholy of people who gazed on it’ and that its maker ‘was terrified (Oh, but there was joy mixed with the terror also) by the miracles worked by the Laughing Christ that he himself had carved’. From the start we are to associate this figure with miraculous terror-joy that heals the sickness of melancholy.

As the story progresses, the Head Scribbling Giant, Atrox, keeps intermittently accusing Denis: ‘You stole from me the thing I most prized in my life, the thing that has authorized my strange continued life. That was the statue or figure or eidolon The Laughing Christ… I believe that it is the Christ himself in the train of his second sepulture. I buried him, as he had instructed me to do, in the ground of Italy. And after three quinque-centums of years [1500 years] he was to rise out of that ground again and renew the world.’

Denis retorts: ‘You did not bury him in the ground, you buried him in your mind. And I found him there’. Then suggests: ‘we will ask the Laughing Christ just what he is and how many authors he had’. Atrox still insists: ‘The Christ was alive when I buried him, at his request’.

The significance of these strange little exchanges to the central theme of the novel—the need for new Scribbling Giants who write the future of the world, the need for a renewed mythology in a world that is languishing on mere ‘facts’—does not leap out at one right away. This is merely hint and echo: an insistent implication that the prized, authoritative source of a Scribbling Giant’s life is the Laughing Christ who will renew the world. As the obverse to mythological beings finding their life ‘hid in Christ’ so the living Laughing Christ is hid, buried, in the heart and mind of the Scribbling Giant who writes the future, an apocalyptic future of renewal (a recurring theme in many of Lafferty’s novels). If this figure is dislodged from the Giant’s possession, he feels it as a worry and ache and irritation that signals a missing element that must be restored. Thus it seems that the health-giving mythology for the naked and emaciated modern world finds its source in the Laughing Christ. (‘Mythology’ in this case does not necessarily signify something that is ‘pretend’ or ‘make-believe’, but rather that which is a vehicle of truth, a lively and fulsome and dramatic metaphor for what is really real, which can co-exist and even be rooted in actual history [see Lewis’s essay]).

When the novel later returns to this subject matter, Lafferty quotes from John Masefield’s 1911 poem ‘The Everlasting Mercy’:

‘O Christ, the plough, O Christ, the laughter

Of holy white birds flying after.’

Then Gorgonius inquires: ‘The Christ, where do you have him on display… He raises so many questions.’

Indeed. He is meant to.

When the statue is interred ‘all eleven of them (including Denis who had carved the statue) drew their breaths in sharply at the sheer beauty and joy and friendliness of the masterwork. Well, this was the most pleasant piece of statuary that any of them had ever seen, slightly larger than life-sized, and wrapped in the colored cleanliness of its own laughter. The Laughing Christ! But who was he really?

‘“No, he is not Christ. He is creature,” Laughter-Lynn said, “and he is alive. Oh, the wonderful eeriness!”’

And it is here that the Faun emerges from the statue. After that interesting episode we are reminded: ‘But the wonderful statue, the Laughing Christ of Creophylus still remained a thing of overwhelming joy.’ That night, having been re-buried, the statue is now brought up once more and the ‘flickering torch-light made it seem as if it were a live man laughing. And all ten of them… were again stunned by the sheer beauty and joy and friendliness of the masterwork.’

So, the statue is indeed merely some weird preternatural creature (in his final scene he has become a member of the questing ‘Group of Twelve’ and partakes in a Mass with them, having ashes and sackcloth put on him by the others), not the Christ himself. (Atrox is presumably just a bit muddled about this, but we might say that his heart’s in the right place.) Yet surely we are meant to think his overwhelming beauty, joy, and friendliness derive from his divine namesake, the real Renewer of the World.

The Faun who came out of the Laughing Christ dies, but the hope is expressed: ‘Maybe some other cheerful spirit will come and live in him’. The statue-creature, as representative of his namesake, will continue to host and house the remaining myth-creatures of the world until its renewal.

Saint Joseph's Great Circular Stairway Built With Only Three Nails

There is one more scene connected to this theme. At the seaside house of Oosterend, the Group of Twelve is asked: ‘Have you seen our Great Circular Stairway that possibly was not built by living hands?’

It is a strange and impossible marvel of architecture: ‘It is one of the Three Wonders of our house and one of the Seven Wonders of the World. It runs from the Monsters’ Den which is two levels below the booming ocean itself to the Sky Studio that is unsupported save by the winding stairway… I came home one evening and there was the beautiful Circular Stairway completed. And there was the Sky Studio new in the sky like a large head on the end of a long corkscrew neck. The whole thing would have taken a crew of five carpenters five weeks to do, except for the portions of it that would have been quite impossible to do at all.’

‘It was Saint Joseph who did it’ they are informed (he was initially recognised by his frugal Galilean pipe and tobacco). As a stranger passing through, he was asked to fix a step in exchange for a meal and so he brought out a small package: ‘It contained a small saw, a small hammer, three nails, a very small board of wood, and two little panes of glass, one of them clear and one of them clouded. I noticed the name on his small package, Joseph Jacobson, so then I knew for sure that he was Saint Joseph; for the father of Saint Joseph was named Jacob. ’

The man of the house who had commissioned this afternoon’s repair work relates: ‘in my sleep I heard a hammer with a melodious ring to it, very pleasant. But even in my sleep I wondered “He has only three nails, and how can he be doing so much melodious hammering with them?” When the man rose from his nap he was told: ‘Really I did a little bit more than fix the step. I built a new stairway.’

The man further recalled: ‘I saw the Circular Stairway then and was delighted almost out of my skin. It was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. I went up to the floor above me and I went down to the floor below me. I did not notice then that it went very much further up and down. “I believe that you are the best carpenter who ever lived,” I said. “No,” he told me, “my son was a much better carpenter”.’

It is a quiet episode of strange beauty and wonder, of magic and miracle (based on an actual legend). Again, we have hints and echoes. The stairway reaches down to monstrous ocean depths (where reside not only sea monsters but ocean-ogres and ocean-nymphs) and up into creative skies (in the Sky Studio they shortly find the scribbling giant Atrox in the midst of writing a resurrection of one of the murdered human characters)—and it was built with only three nails. The discreet allusion to the three nails with which Christ was crucified crescendos into a little punch line about Joseph’s adopted son, Jesus, trained in his own profession, but ultimately capable of far greater wonders of miraculous construction and creativity and connectivity between ocean and sky, earth and heaven, fact and myth, modernity and faerie, psyche and cosmos.

Often There Will Emerge a Face

Between Joseph’s allusive three-nail wonder-carpentry and the recurring figure of the Laughing Christ, Lafferty subtly weaves in both the passion and the laughter of the Christ, the crucifixion sorrow and the resurrection merriment (and thereby, his constant note of carnival—see Andrew Ferguson’s dissertation 'Lafferty and His World', page 25ff.), suggesting that these twin achievements and qualities are what rebuild and renew the fallen world, what reconstruct and reunite all that is ancient and future. I just began reading Lafferty’s The Fall of Rome the other day and was surprised (but not really surprised) in this connection to run into the following in its prologue:

‘Near the end of the fourth century, the Mosaic-of-the-Great-Picture came into its own… The great mosaics were made up of thousands of small cubes or tesserae imbedded in a matrix of plaster or cement or clay. The colored cubes formed intricate pictures, one picture merging into another: these smaller pictures, when seen from a distance and in the right aspect, would form one great picture. Most persons could see it clearly: some could not see it at all… The smaller pictures were of people, animals, actions, furniture and handicrafts, towns, fields, banquets, worships, labours and pleasures, buildings, ships, plows, soldiers, children, courtesans, sheep, and asses. They combined in the great picture (which not everyone could see), the face of Christ… Sometimes the picture of the passion and death of the Empire will be the face of the crucified Christ: but often there will emerge the most fulfilled, the most shatteringly profound image ever, the laughing Christ of Creophylus.’ (pp. 3, 5)

Intricately knowledgeable as he is of such forms of art as the mosaic, I think Lafferty intends to foster the ability of our readerly sight to eventually put together his individual tesserae (the many beautiful, strange, and gem-like stories, as well as the equally crystalline—if frequently opaque—episodes, images, and so on in his novels) into larger pictures (the consistently recurring themes and threads) that merge into each other and eventually form a Face. A Laughing Face. Some see it clearly. Some cannot see it at all.

As the eminent s.f. critic John Clute so aptly observed of Lafferty: ‘his conservative Catholicism has been seen as permeating every word he writes (or has been ignored)’ (Encylopedia of Science Fiction). But if we care to really understand why Lafferty's work delights and moves us so, we ignore this permeation at our peril, for, as Clute also observed: 'his Roman Catholicism governed not only the surface of his work, but its deep structure as well' (obituary).