Even the names of the characters add to the oddity in the air of the narrative: Pilgrim Dusmano, Aubry Pim, Cyrus Evenhand, Howard Praise, Rhinestone Suderman, Noah Zontik, Mary Morey and many more.

The protagonist (Dusmano) is an unlikeable political villain, which makes for unpleasant reading sometimes. Then again, the lampooning of media-manipulated spin of political-celebrity identity is some of the most enjoyably acerbic I've ever seen. There are Media Lords and cults of personality and at one point a meteorological Hand of Heaven pointing down at the political candidate, which has been contracted in advance. This manufactured divine approval is a central motif of the novel. It's a viciously satirical study of the intersection not only of media and politics, but also of theologies, both bogus and true.

To swoop it all in! That would be the last great commercial stroke for Pilgrim Dusmano before leaving the world. This would be the real final pleasure, a break-bone and blood-suck pleasure. The red joy of it, gathering in all the fine property with its long roots with bits of flesh still clinging to them, would go far to nourish even the parallel Dusmanos on alternate worlds or aspects. It was a corporate good, really (p. 89).

It's not all dialogue and terminology and commentary, of course (though there's a ton, which is often the case in Lafferty). Vivid (but usually brief) scenes of action are furnished now and again as well:

The scarf that Pilgrim had been twisting in his hands now overflowed or exploded into a mantle or a cloak. Arrayed in this, Pilgrim went right through the walls of the Prismatic Room and the Personage Club in incipient flight. Noah Zontik stepped to a window and watched Pilgrim ascend the incandescent blue air of the outdoors in slanting, soaring flight. He had a finesse beyond that of any bird. A bird doesn't understand how to pose in the air, how to get the most from his natural lines, how to live a lyric in quick stanzas of flight. Pilgrim covered half a city in the ticking off of a dozen seconds. It was perfection... Pilgrim Dusmano, halfway across town, descended from his flight into the interior of an unspecified house. He quickly killed a startled man there.

"A bit casual, was it not?" the victim rasped with his dying breath (p. 24).

Or witness a snippet of the boar hunt that takes place as part of the festivities on Hieronymous Bosch Day in one alternate world:

Parrots were like flights of fat green arrows in the air. Dogs had a catchy bark on every gasping breath... But the present and embattled boar wheeled again and killed several of the harrying peasant girls and lads. It left them awkwardly broken in the sunny grass. The boar coursed again, and it foamed, not with weariness, but with fury.

Lorica, on a steep bay horse, closed in on the boar and let his horse overrun itself and become impaled on the wheeling boar. At the moment of overrunning, Lorica's lance went into the boar in snout and mouth and throat, but the bogus-stone lance head did not touch the boar brain in any way. That animal, disdaining even to notice the lance, was into the horse with long tusks, richly and redly into the belly; and it raised horse and rider high into the air as it reared on giant bristled hams and small feet (152-153).

Foremost of the threats was a hulking apelike creature that the polymorph saw high ahead. (This was all by firelight, there being no sun in the iron sky, so the seeing and the seeming ran together.) The ape-thing was moving down the terrible and steep path toward the three climbers. It was coming fast enough to intercept them at the Narrow Corner. The path was fearfully narrow even where the three climbed it. The ariel had her crest drooping and smoking; the dog had his singed tail between his legs; the polymorph himself had teeth in his heart that crunched it and gnawed it away (p. 123).

Oh heck, there's even a bit of loveliness thrown in here and there:

She was freckled and unaccountably brilliant. She was dappled and sunbeamed. She was daylight itself, freckled daylight with clouds roiling up behind her (p. 150).

I really can't begin to convey how chock full of delightfully inventive jargon and mind-bending ontology this novel is. It simultaneously hurts and thrills the brain. You often feel as some characters are early on described as feeling: 'There was a bit of horror gnawing at them in the area there, but also some ultra-purple fun' (p. 10).

I leave you with a final sample of the visceral carnival ontological chatter that bristles throughout the book:

Let me tell you a little bit more about the Prime World of prime people, Pilgrim. It is the uninfused world, the grubby world, the spiritualist world, the quack world, the Fortean world. That world is real, and all others are shadows of it. You say this, but you are afraid to mean it, and you are afraid to acknowledge yourself a citizen of it. But your only alternative is to own yourself to be a reflected and not a real person. On Prime World, fish and rocks and blood do indeed fall on the earth out of low and stationary skies. For these are stale skies and do not turn. One can reach those skies with stones thrown by a ballista, and such shots will bring other stones falling in showers onto prime earth. Everything moves very slowly on prime, like objects moved by poltergeists. It is like things moving underwater. It is things moving in prime atmosphere and the reek and heaviness of it. There are vulgar shouts out of that lowering sky. Why not? There are giants living up there, dimwit giants who are the original people. What, Pilgrim - would you swallow only half a camel? And what will you do with the rest of it? (p. 24).

18 comments:

I don't always have something to add (you are much more well versed in Lafferty than I) but I wanted to say I really look forward to these posts. Out of curiosity, how would you rank his novels on a "brain-melting" scale?

Thanks for saying so, Antonin! I never quite who (if anyone) is reading. But I'd definitely do it even without a readership. It's one of the pure labours of love in my life. Anyway, your brain-melting ranking question is awesome! I'm going to meditate on it post-haste!

*know* who (wish you could edit comments)

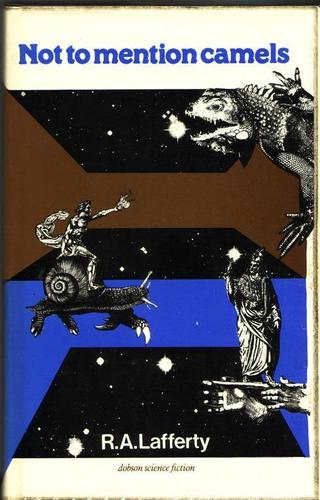

"Not To Mention Camels" is the first Lafferty's novel I ever read. & this book gave to my life a strange direction. I remember I was sure RAL was a pseudonym of Thomas Pynchon who was at that time - & still is - my favorite author. I had found lots of coincidences - the bizarre names, situations driven by the words itself instead of the story, etc. I bet with friends (of course nobody had never heard of Lafferty. I persuaded myself… & lost some bottles of champagne! When I finally realized RAL was a real person, who was still alive (it was around 1990), I couldn't believe such a genius was at this point underrated. So I have translated & published in French some short stories, then a beautiful edition of the Fourth Mansions - sold less than 600 copies - spent a lot of (my wife's) money in purchasing rare first editions of all I could find. I still don't understand why people say Lafferty's novels - particularly Camels - are difficult to understand. They probably - like the young children of Camiroi - haven't learn to slow down their reading speed… I discover your blog today. Sure It will be another glorious day in my reader life. Alleluya !

So glad you found us, Jean-Paul! Huge respect to you that you've translated and published Lafferty. I think you're right that the main problem with his novels is *our* reading. We haven't learned the skill yet. With time, I think we can...

It's an honor for me, Daniel. The main problem is what are we talking about when we say an author is difficult to read. I remember in the eighty's everybody saying Jacques Lacan was completely unreadable… Who could say that today, when most of his concepts are now in common use (same thing with Heidegger, no ?) First response : a question of time - a reason why great authors are condemned to a period of purgatory when they die. The case of Finnegan's Wake is harder to solve : a question of etymology and a puzzle created by mixing the words' roots. Another reason to consider a book difficult is when you don't have the knowledge needed by the subject. Einstein's general relativity theory is an example of this difficulty. Then you can be totally disappointed by the style, that is to say the special way an author transmits his private point of view, and this has something to do with poetry. Coming back to Lafferty, I think his writing is infected with all those problematics. Ktystec machine is probably easier to understand nowadays than when the novel was written. Most of the names of the characters are carefully created with a perfect command of etymology, Fourth Mansions refers to theology, and demands to the reader a good knowledge in christian mystic to be fully appreciated, and my opinion is Camels is a try to write a story that reflects or illustrates the quanta theory… So Lafferty, who set extremely high standard for himself demands the same quality from his readers. Perhaps it's the reason why he has not yet found a real popular success...

Yeah, definitely. But take someone like Gene Wolfe - many readers have tried him out and given up frustrated, wondering what all the fuss and admiration is about. Yet he has a large devoted readership who step up to the high demands he makes of readers. They relish this in fact. And the same is true of most 'difficult' greats, like Joyce or Faulkner or whoever. (Cormac McCarthy is my main 'literary' author that I've spent lots of time with and that some find too difficult.)

But it seems to me that Lafferty is the *even more* rare writer who has so thoroughly invented a new way of perceiving the world in general and of telling stories in particular that one has to become sort of initiated - nay, *baptised* into - his very mode and narratology in order to really track with him. Even many of those who love his work seem to often just think that Lafferty's novels are simply 'Lafferty being crazy Lafferty, ha ha!' It's wild stuff, no doubt. But there *is* structure and control and, in my opinion, powerful effect - and not just in a fragmented 'random' way.

All your summations of what he was doing in each of the novels you mentioned (the ubiquitous etymology, the theology in Fourth Mansions, quanta in Camels) are spot on, but there is the even deeper fact of the *way* he used these tropes or explored these themes. He was a true pioneer. He dug into, tore up, and hurled literature into truly new directions and shapes and I'm not sure the world is going to be able to follow him into the New Country he discovered. I hope we can and I hope we will...

Jean-Paul, I like your theory about RAL being TRP. Even if I know it isn't true, I might believe it anyway (Pynchon is also one of my very favorite writers).

As to the difficulty question, I think that most readers today interested in "Sci-Fi" and "Fantasy" are most attracted to books that have a)interesting characters that they can identify with and follow for multiple books, and b) complex imaginary worlds that have concrete rules when it comes to invented technology, magic, etc. One needs to look no further that Brandon Sanderson's latest topping the NYT fiction bestseller list to see this in action. People who got into speculative fiction through The Wheel of Time or Harry Potter are looking for a very specific type of book that flows like an adventure film.

Lafferty isn't, in short, film-able. His worlds don't behave according to easily followed rules. The characters aren't believable. (In fact, they often make the players in more mainstream SF look quite normal in comparison.) There is rarely a "bad guy". There is an abundance of metaphysics. And so on.

"When film ends, here begins literature", good definition, no ? It could explain why "The Border Trilogy" is so superior to "No Country" (in my opinion).

The fact is Lafferty can't be compared with nobody else. And he has not yet any followers. Strange situation. For himself. And for his fans too.

Alone like half a camel ?

I think some of Lafferty is adaptable to film, but it'll never happen because it would require visionary auteurs and they'll never give Laff a look, or if they do and they fall in love with him, they'll not have the money to throw away on a brilliant film that few will watch and fewer will appreciate. (Witness the critical and popular panning of the BRILLIANT, if flawed, McCarthy/Scott film The Counselor.)

Jean-Paul, I still haven't read the Border Trilogy or Suttree - I've read everything else by McCarthy. No Country's great, but it's probably his lightest book.

Since the likes of Neil Gaiman and Gene Wolfe and Harlan Ellison have professed to be fans of Laff, I don't see how he doesn't get a bit more of a cult following (I think our few numbers don't even amount to *that* much, ha!).

As to Lafferty's characters not being believable... that got me thinking so much, I'm gonna write a whole post about it!

Haha, glad I could help!

I can't really think of any filmmakers that could do Lafferty justice, visually. On the one hand, his characters and settings are very vivid. On the other, they have an ethereal quality that is very hard to pin down. What is it supposed to mean, exactly, that Amelia Lilac "seemed always to be wrapped in a lavender cloud or shadow"? Does her skin glow? Is she literally surrounded by purplish vapor? Or is this a mental impression Quiche gets based on her personality, how she carries herself in conversation? And that is a very tame example, for Lafferty.

Panos Cosmatos might be able to do them justice. I was hugely impressed by his only film so far, Beyond the Black Rainbow. Daniel, you might want to consider it for your horror blog, if you haven't seen it already.

Terry Gilliam also comes to mind. He seems to be able to strike a great middle ground between the grotesque and the hilarious.

Yeah, you'd almost have to have this impossible selected blend of film makers - a fusion of various aspects from the likes of the Coen Brothers, Terry Gilliam, Tim Burton, Martin Scorsese, Guillermo Del Toro, Quentin Tarantino, David Lynch, Joss Whedon, Tomas Alfredson (Let the Right One In) and a probably bunch of other 'world cinema' film makers I know nothing about, like Cosmatos that you mentioned (thanks for the movie recommendation). I bet there are some Japanese directors who could do some amazing stuff with Laff (and he appears to have a very enthusiastic Japanese following.) Not to mention elements of dead directors like Kubrick and Hitchcock and Leone.

But yeah, I made sure to say this was about *adapting* Laff to film. So much of the linguistically conjured texture such as you cited about character descriptions would have to be severely muted if not lost altogether. And it'd be about picking certain stories over others, etc.

It'd be interesting to make a list of gonzo movies that seem plausibly Laffertian - like Buckaroo Banzai, O Brother Where Art Thou, Big Fish, Time Bandits, The Straight Story (think about those old timers in that shop talking about the grabber), the first half hour of Fire Walk with Me (aspects of Twin Peaks to add a TV show), Kill Bill II, Cabin in the Woods, etc etc

Yeah, Lynch was another who could be, if nothing else, brave enough to try it. I've only seen Twin Peaks and Mulholland Drive of his, but particularly the latter is dreamlike enough, with unconventional horror elements, to evoke parts of Lafferty. Do you have any info on Japanese Lafferty fans? I'd love to see the covers!

Dude, I hit the jackpot on Japanese Lafferty covers the other day. They're going up on the Facebook page soon:

AmazonLafferty

Whaaaaaat? Those are amazing!

I have some pix of japanese covers on my site too. It is just work in progress and… in french (sorry) !

The address is :

www.eastoflafferty.com

Wonderful site! Thank you for the link!

Post a Comment