Dostoevsky meets Chesterton

Let’s start with a hefty dose of a few Old World masters of moral-spiritual fiction: Dostoevsky and Chesterton. Think of the deep, dark, and tenacious quest for God in a post-theistic world in the former mixed with the biting, satirical, joyous exuberance, wit, whimsy, farce, fancy, and wildness of the latter. (And, in terms of being predecessors to Lafferty, it is no coincidence that both of these great authors were creative adherents to Christian Orthodoxy.)

Let’s start with a hefty dose of a few Old World masters of moral-spiritual fiction: Dostoevsky and Chesterton. Think of the deep, dark, and tenacious quest for God in a post-theistic world in the former mixed with the biting, satirical, joyous exuberance, wit, whimsy, farce, fancy, and wildness of the latter. (And, in terms of being predecessors to Lafferty, it is no coincidence that both of these great authors were creative adherents to Christian Orthodoxy.)

American Tall Tale meets Native American Folklore

Does this sound a bit serious and weighty? Well, Lafferty was such. But he is also constantly called ‘mad’, ‘insane’, ‘zany’, and the like. And he has the reputation of making the reader laugh aloud. So much so that the weightiness of his art has not often been appreciated. Chesterton’s influence can certainly account for some of the ‘lunacy’ and laughter. But for his unconventional qualities we must now also mix in the ingredients of American tall tales and Native American myth and folklore: Paul Bunyan meets Coyote the Trickster as it were. Think of the larger than life, hilarious, and gigantesque frontier exaggeration of the former mixed with the sly, wry, tribal, traditional, spiritual, ancient magic and mystery of the latter.

Does this sound a bit serious and weighty? Well, Lafferty was such. But he is also constantly called ‘mad’, ‘insane’, ‘zany’, and the like. And he has the reputation of making the reader laugh aloud. So much so that the weightiness of his art has not often been appreciated. Chesterton’s influence can certainly account for some of the ‘lunacy’ and laughter. But for his unconventional qualities we must now also mix in the ingredients of American tall tales and Native American myth and folklore: Paul Bunyan meets Coyote the Trickster as it were. Think of the larger than life, hilarious, and gigantesque frontier exaggeration of the former mixed with the sly, wry, tribal, traditional, spiritual, ancient magic and mystery of the latter.

With these two major streams of Old World authors and New World folklore (you might call them ‘high’ and ‘low’ respectively, in terms of ‘register’) you can already see how Lafferty’s is going to be fiction that doesn’t easily fit moulds and that needs very large, wide-open spaces of thought and imagination to breathe and move and play and preach and fight and astound. But we’re far from through concocting this utterly strange brew.

Vaudeville meets Carnival

Keeping in the register of ‘Cowboys and Indians’, bring in the Vaudeville variety show and the Carnival barker. It’s the comedic, popular fun and 'burlesque' (as in absurd parody and exaggeration: there's no striptease in Lafferty's stories) of the former mixed with the freakish grotesquery and weird wonder of the latter—and the call for the audience to participate in both. There's song and dance and feasting and drinking and brawling and bragging a plenty in Lafferty's tales.

Irish meets Greco-Roman

Now let’s reach back to the much older Old World for influences before we finally charge into the latter 20th century context of when Lafferty was actually writing. Lafferty the Oklahoman was of Irish Catholic descent and it shows. The Irish storyteller is in him and he’s often been compared to both Flan O’Brien and James Joyce. You can also hear resonances in the contemporary playwright, Martin McDonagh. There is often even an Irish lilt or brogue to Lafferty’s cadence, syntax, and word choice.

In terms of wording and style and content we must also look back to ancient Greco-Roman sources of all varieties—plays, myths, philosophers, church fathers, politicians, treatises, epics, satires, ‘histories’ and so on. Thoughts and ideas from these ancient sources abound in Lafferty as well as everything else we’ve mentioned up to this point. The Bible and Medieval literature also make their influences felt, adding both a Hebrew and European flavour. And it’s worth mentioning here that there is some Arabic influence to be found also, perhaps mainly from the Thousand and One Arabian Nights and from Muslim culture of the Charlemagne era. From these Old World sources too I think comes Lafferty’s great interest in languages (partly by a working knowledge of which he re-invented the language and syntax of English Literature fiction to suit his own purposes).

American New Wave Science Fiction meets Southwest Regional Fiction

%5D&sink=preservemd%5Btrue%5D)

A Ferocious, Generous, Joyous Storyteller

Does all this sound like perhaps a little too much broiling and roiling inside one man, too much for one artistic output? Well, frankly, sometimes it is! Lafferty at his very best (usually in his short stories) has a gemlike quality of concentrated power that swiftly and furiously, but smoothly, weaves and blends and infuses all or most of these streams of influence into an exquisitely coherent piece of art. It is truly awe-inspiring when it comes off. Really. But often his fiction is over-full, bristling, and careening with this background and all his feral genius firing and flailing.

‘Come on, y’all, this is awesome’

In closing, I want to mention that contemporary giants of ‘alternative’ dark fantasy such as Gene Wolfe and Neil Gaiman have cited Lafferty as a hero and influence. Both Wolfe and Gaiman have attempted to write stories in the ‘Lafferty genre’ (he really did essentially invent his own genre – in many ways he is the Captain Beefheart of American literature).

‘It’s hilarious, incredibly funny and at the same time it’s insanely dark… You get such a sense of joy and boundless imagination in every sentence – even if the story doesn’t totally cohere, you feel like it’s about something. It’s so incredibly Tulsa. You get that feeling when you see a Flaming Lips show. It’s not like we’re dark and hurt and twisted. It’s like, “I’ve got blood on my face – come on, y’all, this is awesome.”’

Lastly, we mention not so much influences as context—but a context that very much shaped the contours of Lafferty’s fiction. Lafferty’s fiction emerged mostly in the science fiction magazines of the 1960s among a constellation of ‘New Wave’ writers who were experimenting with new directions in the genre, focusing more on the ‘soft sciences’ of language, psychology, and anthropology rather than the traditional ground of science fiction in the ‘hard sciences’ of physics, technology, and so on. Harlan Ellison and the authors that populated his Dangerous Visions anthologies such as Roger Zelazny and Samuel R. Delany warmly welcomed Lafferty into their midst and praised him almost without qualification and with some genuine awe at the raw potency of his imagination and originality.

Many of these New Wave s.f. authors have a strong feel of the Beat Generation stylisings of the likes of William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac—and you often hear echoes of beatnik and jazz talk in Lafferty, but it is mostly just played with; his real roots are in the aforementioned, which arguably enabled him to out-jazz the ‘cool’ set at their own game.

But ‘cool’ Lafferty was not. He might be mistaken for such at a glance, but he was actually quite a bit older than most of his fellow writers of the time and really was doing something that was strange in a truly bizarre and pungent mode, not just a bit zany in a ‘hip’ sort of way. His experimentation, frankly, went far deeper and was more truly radical and structural, not least by being rooted in and nourished by potent traditions rather than attempting any kind of clean break with the past into a ‘new age’ or ‘summer of love’ or what have you. He was searching for bigger, muskier, shaggier, bloodier, spookier, gladder, subtler game.

One way he wasn’t as ‘hip’ as his contemporaries was by being far more of a ‘regional’ writer, particularly of his native Oklahoma and Southwest region. The open feel of the plains and prairies, of cattle and horses and horns and hooves, of fishing and hunting and living under the open sky, of saloons and ropes and saddles, of bucks and buffalos and bears, of Native Americans and ranch hands and cowpokes and so on, all permeate his fiction. Indeed, I felt so many tactile resonances with Lafferty’s fiction when recently reading Cormac McCarthy’s anti-western novel Blood Meridian. That was really when my eyes were fully opened to Lafferty as a regional writer of the Southwest. This places him, with all his other associations, loosely alongside some of his fellow Catholics who were Southern regional writers like Flannery O’Connor and Walker Percy.

%5D&sink=preservemd%5Btrue%5D)

Does all this sound like perhaps a little too much broiling and roiling inside one man, too much for one artistic output? Well, frankly, sometimes it is! Lafferty at his very best (usually in his short stories) has a gemlike quality of concentrated power that swiftly and furiously, but smoothly, weaves and blends and infuses all or most of these streams of influence into an exquisitely coherent piece of art. It is truly awe-inspiring when it comes off. Really. But often his fiction is over-full, bristling, and careening with this background and all his feral genius firing and flailing.

Lafferty's world is one that feels like absolutely anything can happen, and yet it has an underlying coherence and solidity – it’s not a drugged up, tripped out psychedelic fantasia. It’s meaty, earthy, punchy, mythic, transcendent, wry, jokey, gruesome, funny, wily, ornery, amiable, farcical, grave, gritty, grotesque, delightful, magical, realistic, wild, noble, uncanny and canny all rolled into one. Indeed, this makes it something of a minor miracle that he can write an almost-mediocre story now and again (though there’s almost always a memorable wonder in there somewhere). His short story collections are the best place to start before moving on to the usually less cohesive, but equally wonder-filled, novels.

Lafferty can make you laugh harder and think harder than you’re used to, and also amaze your imagination and sense of wonder like few ever will. He called himself ‘the cranky old man from Tulsa’ and yet he fought hard to imbue the world with highly creative and inventive hope for a spiritually renewed present and future, calling all who would hear to join in world-up-building with all their powers and faculties on full throttle. He was a ferocious and generous and exuberantly joyous storyteller who spun out whopping tales at breakneck speed in a tumbling torrent of wild and glad and angry urgency and ecstasy. We are truly blessed to have had him. We must make the most of what we can get hold of.

In closing, I want to mention that contemporary giants of ‘alternative’ dark fantasy such as Gene Wolfe and Neil Gaiman have cited Lafferty as a hero and influence. Both Wolfe and Gaiman have attempted to write stories in the ‘Lafferty genre’ (he really did essentially invent his own genre – in many ways he is the Captain Beefheart of American literature).

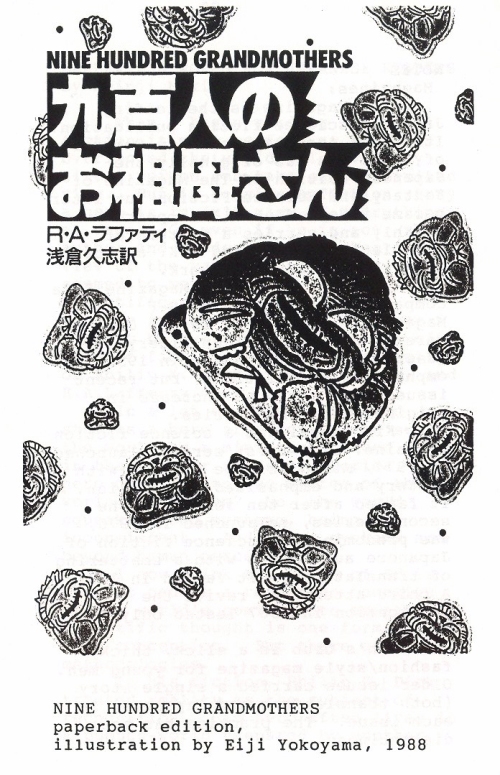

A few years ago, the New York Times asked the Saturday Night Live comedy actor, Bill Hader (a fellow Oklahoman), what books he recommended and he started his list with R. A. Lafferty’s collection of short stories entitle 900 Grandmothers. I’ll leave you with his apropos words trying to describe the experience of reading Lafferty:

‘It’s hilarious, incredibly funny and at the same time it’s insanely dark… You get such a sense of joy and boundless imagination in every sentence – even if the story doesn’t totally cohere, you feel like it’s about something. It’s so incredibly Tulsa. You get that feeling when you see a Flaming Lips show. It’s not like we’re dark and hurt and twisted. It’s like, “I’ve got blood on my face – come on, y’all, this is awesome.”’

10 comments:

I didn't reaiize that Gene Wolfe tried a story in the Lafferty style. Which story is it? I wouldn't mind reading it, although I've read almost nothing of Gene Wolfe.

Neil Gaiman was the writer behind one of my favorite films (Mirrormask) and was the reason I read Lafferty now. The story which he attempted in the Lafferty genre (Sunbird) was far and away the best of the collection in which I read it (Fragile Things). In fact, it's not a terrible introduction to Lafferty himself, although I still consider "Seven Day Terror" to be ideal in this regard, with "Land of the Great Horses" as another worthy option. Zebediah T. Crawcrustle is a Lafferty character (with some resemblance to Willy McGilly), and if you can write a Lafferty character, you're halfway to a Lafferty story. Additionally, I thought Virginia Boote was modeled in part on Valery Mok.

I'm away from my home library right now so I can't check. If memory serves, it's actually a chapter from Wolfe's novel Peace, but it's reproduced as a short story in a Wolfe collection (maybe Innocents Aboard?) and he wrote somewhere that it was his attempt at writing a Lafferty style story - I can't remember where he wrote that either! I'll figure all this out when I get back home in August and let you know.

Also, though, Wolfe mentions Lafferty by name in his short story 'Has Anybody Seen Junie Moon?' in the collection Starwater Strains.

Wolfe is another literary/s.f. giant for me. I write a whole blog devoted to him also:

http://silkandhornheresy.blogspot.com/

Yes, I've heard so many people say they came to Lafferty through Gaiman's 'Sunbird'. So glad he wrote that and acknowledged Laff's influence.

Also, I'm actually glad to hear you say you think 'Land of the Great Horses' would be a great intro to Laff as it's the first story of the 900 grandmothers collection (which seems to be the one most people try to get hold of first) and I always think 'but they'll be put off by the first story as it's not that great'. I'm always amazed at the wide difference of opinion about what are his best and worst stories.

The Internet ate my comment. Let's see if I can remember it. . .

The first story of the Nine Hundred Grandmothers collection is actually the title story, which I find mediocre. But "Land of the Great Horses" absolutely blew me away the first time I read it, and it's what kept me excited about continuing on. It's also universally liked by everyone I know who's read any Lafferty. And because Ginny is universally disliked by all those same people (although I wonder if that'd be different if they read Revelation 12 first) and Six Fingers and Frog are long, "Land of the Great Horses" is vital to have near the beginning to keep people excited. At least in my experience. Also, it still blows me away on every re-read.

I'm also amazed by the wide difference in opinion, most notably on Fourth Mansions. I just re-read it and continue to think it's fantastic and likely Lafferty's best novel, but a lot of people really dislike it. On the stories, just between me, you, the RAL devotional page, and Andrew, I can think of vastly disparate opinions on "Frog on the Mountain," "The Six Fingers of Time," "Continued on Next Rock," and "Days of Grass, Days of Straw." And I'm sure there are plenty more. I guess when there's so much going on in the stories, people can latch on to a lot of different elements that provoke different reactions.

I'm afraid I'll now have to break your the universal opinion on 'Great Horses'. I first read it in Dangerous Visions and it did very little for me. I need to re-read it but I never recommend it or even think about it. '900 Grandmothers' on the other hand I find far from mediocre - it's one of my favourites. Andrew Ferguson's paper covers it and he clearly thinks it's Lafferty at a high point too.

So there ya go! Yet more wide discrepancy in opinion on what's his best and worst. Go figure.

I read about half of Fourth Mansions, probably around 8 years ago and was pretty bored by it - so much so that I just couldn't finish it. Every other of the six or so Lafferty novels I've read I've found almost no problem to finish in pretty short order - even if I didn't love it (such as The Devil Is Dead - wasn't terribly impressed at the time - but again it's considered a fave by many fans).

Now I'm reading Fourth Mansions again and am about 60 pages from the end. My opinion has completely changed. It surely has some of the finest Lafferty prose out there and is a wonderful romp and meditation on a number of levels. Still, however, I have to admit it does start to get hard to finish in it's latter half. Very excited about it now, though.

Maybe my opinion of 'Great Horses' will change too!

Well, there you go, even more disagreement. I'm a bit surprised that you didn't like "Great Horses," since you said you liked the stories that blew you away. And that one certainly blew me away. When I finished it, I was amazed that anybody could think of that ending, much less pull it off. Keep it mind that it was only my 2nd ever Lafferty story, so I hadn't been exposed much to his style. But it continues to blow me away on future reads. Nine Hundred Grandmothers was my first Lafferty story, and I was a bit mystified by the lack of ending. It treats me better on re-read, but I still don't count it among my favorites.

The ending of Fourth Mansions can definitely be hard. The first time I read it, I loved the first five chapters or so, enjoyed the next several, and had some trouble with the last couple, but still liked the story overall. Upon re-read, because I already had some idea of what was going on, I found the ending much easier to follow, and actually extremely enjoyable. It's probably my favorite ending of any of his stories, with the possible exception of Okla Hannali. [When I say ending, I mean last few pages, not last line. I admit that the last line to The Annals of Klepsis is fantastic]

Yeah, for some reason I'm just not that into Lafferty's endings - not that I mind them at all. It's just that it tends to be what he does in the midst of a story that blows my mind. The 'precursor' dreams in 'Configuration of the North Shore', the descriptions and antics of super slowed down time-flow in 'Six Fingers of Time', the prehistoric monsters falling out of the sky in 'And All the Skies Were Full of Fish', the all-round bizarre alien bear and the whole setting of 'Snuffles' - and so on. Most of these stories end strangely and ambiguously - but it's about the wonders on the way and the overall impression. And this isn't even getting into stories I love more for language or philosophical speculation. Lafferty is just not a plot man for me. (Though I experience a ferocious joy of sheer storytelling in his body of work. I guess there's more to narration than traditional plot mechanics.)

I do think I'll like 'Great Horses' way more on subsequent readings. The idea of what the ending does is truly astounding. It just didn't wow me as a story the first time.

Fair enough. As mentioned in our previous conversation, I'm a sucker for a good ending. And knowing a fantastic ending will also get me more into the remainder of the story on re-read. "What's the Name of That Town" is my favorite for a reason. I agree that endings aren't usually how Lafferty draws you in, as they are indeed mostly strange and/or ambiguous. But he had a couple that were really great, and those stories do draw me in particularly.

Lovely blog you havve here

This blog post provides a fascinating analysis of R A Laffertys writing influences.

Post a Comment