It's finally gonna happen! I'd heard about this, but I just now found out about a lovely page over at

Centipede Press that outlines the project to publish

all 200 of Lafferty's short stories (12 volumes' worth!) over the coming years.

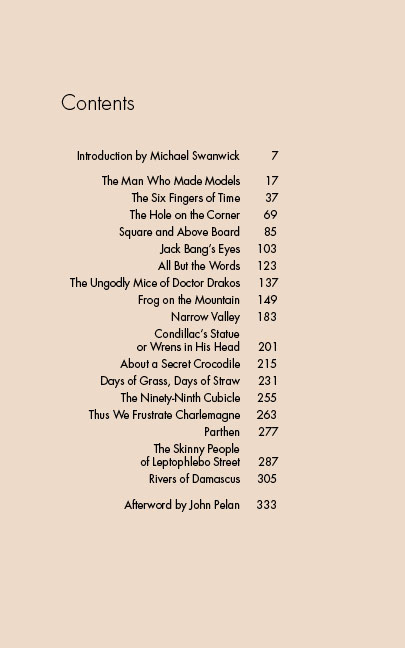

Each volume, they inform us, will include 'a guest introduction by a notable author in the field of fantastic fiction' (the first being Michael Swanwick - you can see an excerpt of the opening paragraph over on the page linked to above). They even give us the table of contents for the first volume:

I have all of these stories in one format or another besides 'The Ninety-Ninth Cubicle', a rare story only appearing in the

Weird Tales Fall 1984 issue or the 1991 collection

Mischief Malicious (And Murder Most Strange) from United Mythologies Press, both now all but impossible to obtain.

I'm very happy to see that some of the more obscure stories are already showing up, even those collected only in the Chris Drumm paper chapbook format from the early 80s (these are like little zines really - quite a cool DIY 'punk rock' sort of format in my opinion, but the typewriter lettering is a little hard to get into as a reader, to really feel like you're reading a genuinely published story and not just someone's unpublished manuscript). The story 'Jack Bang's Eyes' is one of my favourites, especially because of the wonderful chimpanzee character Flip O'Grady. It's the first story in Drumm Booklet # 13:

Snake in His Bosom and other stories.

I'm a little surprised, however, that they're kicking the whole book off with the story 'The Man Who Made Models', the titular story of Drumm Booklet # 18, a story I found rather difficult and not as gob-smacking or exquisitely crafted as many other stories by Lafferty.

It just shows me once again that Lafferty fans differ so very widely as to what is his best work, or where to start with his work. But I'll have to go back and re-read 'Models' thinking of it as the first story in this volume and see how it hits me. I'm glad they go on to 'The Six Fingers of Time' right after that. It's a story I've used to introduce and hook quite a few people to Lafferty. Straightforwardly written and packing a vivid imaginative punch with its well-imagined slow-down of time and movement, with characteristic playfulness and mischief and, of course, rather diabolical consequences (and a poignant little love story too). 'The Hole on the Corner', next in line, is a classic and well-loved tale, which really shows off some of the outrageously weird lengths Lafferty can go to in two seconds flat. Very funny, uproariously gruesome, wildly imaginative, unsettling. Both 'Six Fingers' and 'Hole' are from the ever popular first collection of Lafferty's short stories

Nine-Hundred Grandmothers (1969) and unsurprisingly, they're not the only ones on the list. 'Square and Above Board' was not a story that particularly struck me when I read it (I have it in the 1983 anthology

The Year's Best Fantasy Stories: 9), but I'd love to see it again in this new context. I have a feeling most of his stories are going to take on a fresh shine in these new formats and constellations.

I could wish they had at least one more story from Lafferty's 1971 collection

Strange Doings besides 'All But the Words', and also at least one more story from his 1974 collection

Does Anyone Else Have Something Further to Add? besides 'About a Secret Crocodile', and perhaps also one more from the 1991 collection

Lafferty In Orbit besides 'The Skinny People from Leptophlebo Street' (and these are probably not the stories I'd have chosen from those collections if it was only going to be one). But I am happy to see a number of stories that I first encountered in the under-appreciated 1984 collection

Ringing Changes: 'The Ungodly Mice of Doctor Drakos', 'Days of Grass, Days of Straw', 'Parthen', and 'Rivers of Damascus' (two of them being ones I'd definitely have picked). As I said

Nine-Hundred Grandmothers provides the lion's share of the collection with three more stories in addition to the two I've already mentioned: 'Frog On the Mountain', 'Narrow Valley', and 'Thus We Frustrate Charlemagne', the latter two consistently considered classics and 'Frog' being another very worthy choice in my opinion.

That just leaves 'Condillac's Statue or Wrens In His Head' from the 1982 collection

Golden Gate and Other Stories (a book which also first collected 'Days of Grass'). It's a great story, but it continues with the trend of this first volume to collect stories that are heavy on philosophy and complex ideas and narrations. I think this first volume could do with a few less hefty numbers and a few more that are slam-bang

fun - otherwise people might get the wrong idea about what all Lafferty accomplishes across the spectrum of his storytelling.

Then again, I guess this series is really only for those who are already dedicated fans, since it's gonna cost a pretty penny per volume and run into five or six hundred dollars to collect all twelve books. To be perfectly honest, huge fan that I am, I'm going to have to really scrape pennies (and maybe auction off a few children) to keep up and collect each one as it comes out. And that's the only way to be sure of being in on it apparently. This first run is limited to 300! Presumably the subsequent volumes will be similarly limited in number. (If any rich readers want to sponsor my collection, I can promise the Lafferty Library in my hands will go to very good use and be thoroughly reviewed and publicised to the further fame of Lafferty! The rest of you, stop judging my beggarly kowtowing to the wealthy!)

I'm gratified to see 'Parthen' and 'Six Fingers of Time' on this opening list as I've championed them as good starting points over the years and most of my fellow Lafferty fans have demurred. Also, I'm very happy to see 'Days of Grass, Days of Straw' as it deserves to be widely known as one of Lafferty's very, very best.

Looking over the list again, it's also good to note that Lafferty's inimitable bending of space, time, and persons are all represented in these stories - the way he goes sideways and ultraviolet with the classic science fiction and fantasy tropes of time travel and multiple worlds and alien contact and planetary expeditions. There are also several of his Native American-centric tales and those featuring animals to pleasantly odd effect. Also included are tales showcasing how he can stretch and shrink both people and places at will.

All in all it's very exciting! '

This is beginning, this is happening! Let no least part of it ever forget the primordial tumble that is the beginning!'

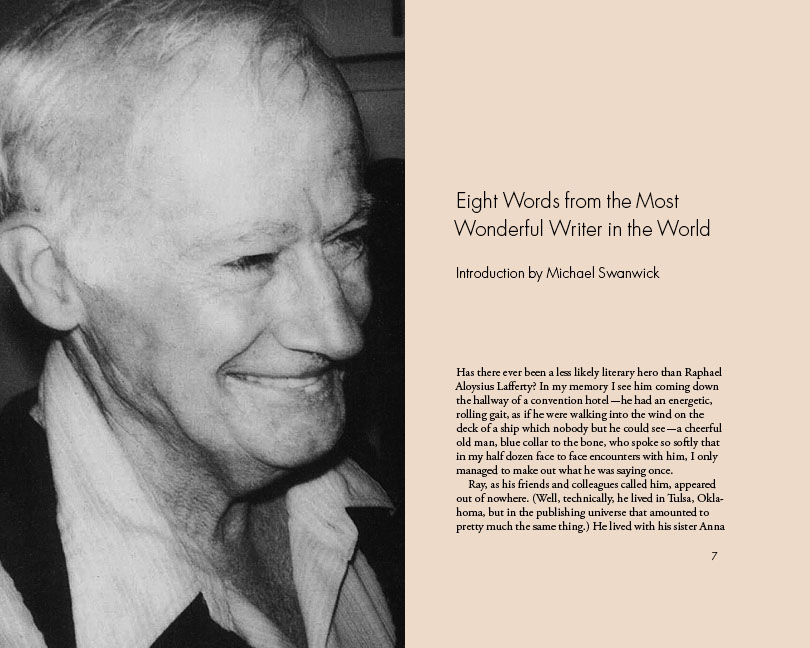

I'll conclude with the photo of Lafferty the first volume includes, which I've never seen before and I find just lovely.